The Anatomy of An Economic Crisis Commentary

Over the past 2 weeks I have read, watched and consumed countless hot takes and expert opinions on what's going on with the tariff wars, and what investors 'need' to know. Does anyone really 'know'? Here I break down the futility of this obsession, and what we must keep in mind going forward.

I will never forget a conversation from 2014 or so. I was having dinner with a friend who was in the midst of taking an MBA program.

She was telling me about a discussion they had that day – the professor asked the class a thought experiment about Ben Bernanke (then Chairmen of the Federal Reserve) in the 2008-09 global financial crisis ‘let’s say that interest rates were as low as they could go, and quantitative easing had gone as far as it could, and there’s nothing else that can be done – what’s to stop Ben Bernanke from showing up to work wearing a clown costume?

Eventually the class settled in on ‘everyone needs at least the illusion that the people in charge were taking the GFC seriously and doing everything they could, whether there was anything they could do or not’.

The illusion of control allows for a confident narrative.

It wasn’t even two weeks ago that Donald Trump announced tariffs on much of their global trading partners, and yes, Heard and McDonald Islands which are inhabited by penguins, not humans.

Stock markets around the globe responded with a sharp sell off in the days after.

The outlook on the economy and the companies within it that build the products and provide the services saw their future profitability and ability to manage cash flows and pay debts fall and thus the values of those companies fell along with it.

The drop in the stock market are the way investors at a global scale say ‘I’m willing to invest in this company, but I’m not paying THAT price anymore’.

This resulted in the S&P500 dropping 6.65% and 5.97% on April 3rd and 4th respectively, and the declines extended into the following week.

Whenever events, big or small appear – the investment commentary and market prognostications are right there with us.

Everyone had a take on what was going on, what we need to know, and the implications of tariffs on our investment portfolios.

Commentaries are loaded with nonsense and often cause more harm than good to those who consume them.

With that – let’s get started on the Anatomy of an Economic Crisis Commentary – and understand why they’re written, how they work, what they say, and what investors should REALLY be taking away from them.

Is this an exercise that the industry insists on which could be equally valuable to the viewer/readers had the person giving the remarks been wearing a clown costume?

The first rule is that anyone on Wall St/Bay St NEEDS to have an opinion, hot take, or solution to the problem. It’s fight or flight time – cooler heads cannot possibly prevail.

There’s a marketing term in the industry which gets repeated a lot on Bay/Wall Street and couldn’t be further from the truth – ‘it’s better to have the wrong opinion on the markets than it is to have no opinion’.

Marketing departments know that people eat up a good story – and an elaborate market commentary with charts and speculation is the grounds for a good story. The consumer of the content needs to know how important ‘right now’ is, and that it’s all hands on deck in their research department.

They’re your guide in the story. They know what they are doing. They’re going to tell you exactly what you need to be doing with your money right now.

The investment teams that write these commentaries trip over themselves to analyze and overanalyze the facts of the day or the things they ‘know’ about an event.

They often come with a caveated ‘obviously we’re in a time of uncertainty’ so that if/when they end up being wrong about can be attributed to this uncertainty. All the while subtly implying that they’ve been correct in past ‘times of uncertainty’ by the confidence in what their saying, or by the implied expert status of being in the position to write or speak to such an audience.

How could they not be?

Surely the media didn’t bring a shmuck off the street – they brought an expert! Someone in the know.

As viewers or consumers of content, we hear all the ways that they will navigate our retirement savings through this crisis of the day with ever conflicting commentaries across the pundits.

One person is saying the market is going lower and not to catch a falling knife while the other is screaming buy low!

But remember, these are ‘times of uncertainty’ so if they are wrong – it’s not their fault, did you not hear about how hard the team is working??

Saying that now or whatever event marks a real ‘time of uncertainty’ comes with baggage and a presupposition that all previous times before it were times of certainty where they sailed along and did no wrong.

The vast majority of investment professionals around the world underperform the benchmarks they are compared against [more on that here and here], so no – they did not navigate ‘certain times’ as much as they likely won’t navigate these ‘uncertain times’.

Regardless of this, they will inevitably end up with a ‘what investors should be doing with their investments right now’ crescendo.

‘Invest in this’, ‘sell that’, ‘we’ve been telling clients to ______’, you get the idea.

The higher the confidence and the higher the conviction, the more compelling it is and the more that we as consumers of the content switch our brains off and absorb it.

The expert has a handle on this, don’t worry.

The commentary ends, they hit publish and high fives all around. If all goes to play, you leave thinking they have solved the economic event.

Economic crisis commentary follows this formula to a tee:

- Here’s what’s happening…

- Here’s why you need to worry…

- Here’s the expert’s analysis…

- Here’s what you should need to do to solve this event…

- Whispers of ‘call me'!

What these pieces of analysis neglect is that whatever the current ‘uncertainty’ is a continuation of a long list of uncertainties of the past which will only continue into the future long after we’re all gone.

Uncertainty is the normal state.

Every headline economic event brings a disproportionate amount of energy spent on figuring out the issues of the day while neglecting that the game is constantly changing.

James P. Carse wrote the book ‘Finite and Infinite Games’ which showed how games like baseball are ‘finite’. 9 innings, 3 outs per half inning, balls and strikes, you get the idea. The rules are constant and understood, and there is a winner or loser at the end.

Infinite games are those which the rules, the gameboard, the players are ever changing with no defined endpoint. There is no winning or losing an infinite game – you win by continuing to play it.

Life is an infinite game.

Our careers are an infinite game.

Parenting is an infinite game.

Tariffs and current day economic events are a ‘finite’ game. A decade from now it will be a different crisis, a different rule book, and different commentary.

But investing is an ‘infinite’ game. We invest for a lifetime.

Essentially, solving for today doesn’t really solve anything when we know that the rules of tomorrow will shift.

The question that should arise is ‘how is that working for you?’

As in, what was the expert forecasting 6 weeks, 6 months, or a year ago when asked to react on whatever was going on at the time?

What was the ‘what’s happening?’/’expert analysis’/’here’s what you need to do’ formula last time, when this current event was an “unknown”?

There’s a passage in Daniel Crosby’s book ‘The Laws of Wealth’ which can’t be repeated enough:

“You might think that the bad news about forecasting couldn’t get any worse, but you’d be wrong. Not only are forecasters bad in aggregate, but the worst forecasters of all are the ones we are most likely to tune in to. Philip Tetlock of UCLA performed the most exhaustive study of expert forecasters to date, examining 82,000 predictions over 25 years by 300 experts. The overarching conclusion of the study is that what you might now expect – “expert” forecasts barely edge out flipping a coin. More damning still were Tetlock’s other findings, that the more confidence an expert had, the worse his predictions tended to be and that the more famous an expert was, the worse her predictions were on average. Only in Wall Street Bizzaro World would we expect confident experts to be stupid and famous thought leaders to be deserving of infamy.”

This is the little secret behind all this talk about commentaries.

The ‘experts’ know their commentary is purely just a guess or are willfully blind to the evidence that screams ‘nobody knows, stop pretending to’.

It puts them at an existential crossroads thinking ‘I’m supposed to be the expert, people rely on me for forecasting expertise, I have to give them something – it’s my job to know!’.

This is not presented to the viewer or reader at the outset however, and there in lies the rub.

It is a legacy of 1990s style ‘my stock broker has good ideas’ mentality. They weren’t good then, and we should know better now.

They unknowingly position themselves as working within a finite point of view. As if once we have reached the end of this specific ‘uncertain time’ all will back to normal.

This brings me back to the beginning. The expert commentaries, and the teams who research and create them haven’t shown the ability to outperform the markets in the long-term, and are basically a coin-flip in the short term.

The act of creating crisis commentaries are purely a vanity project behind the scenes.

Like Ben Bernanke in the MBA thought experiment above, at what point do they admit they have no control over the current situation we are in or whatever future event is going to happen, and write in big bold letters at the start of their written reports that readers should imagine the writer wearing a clown costume.

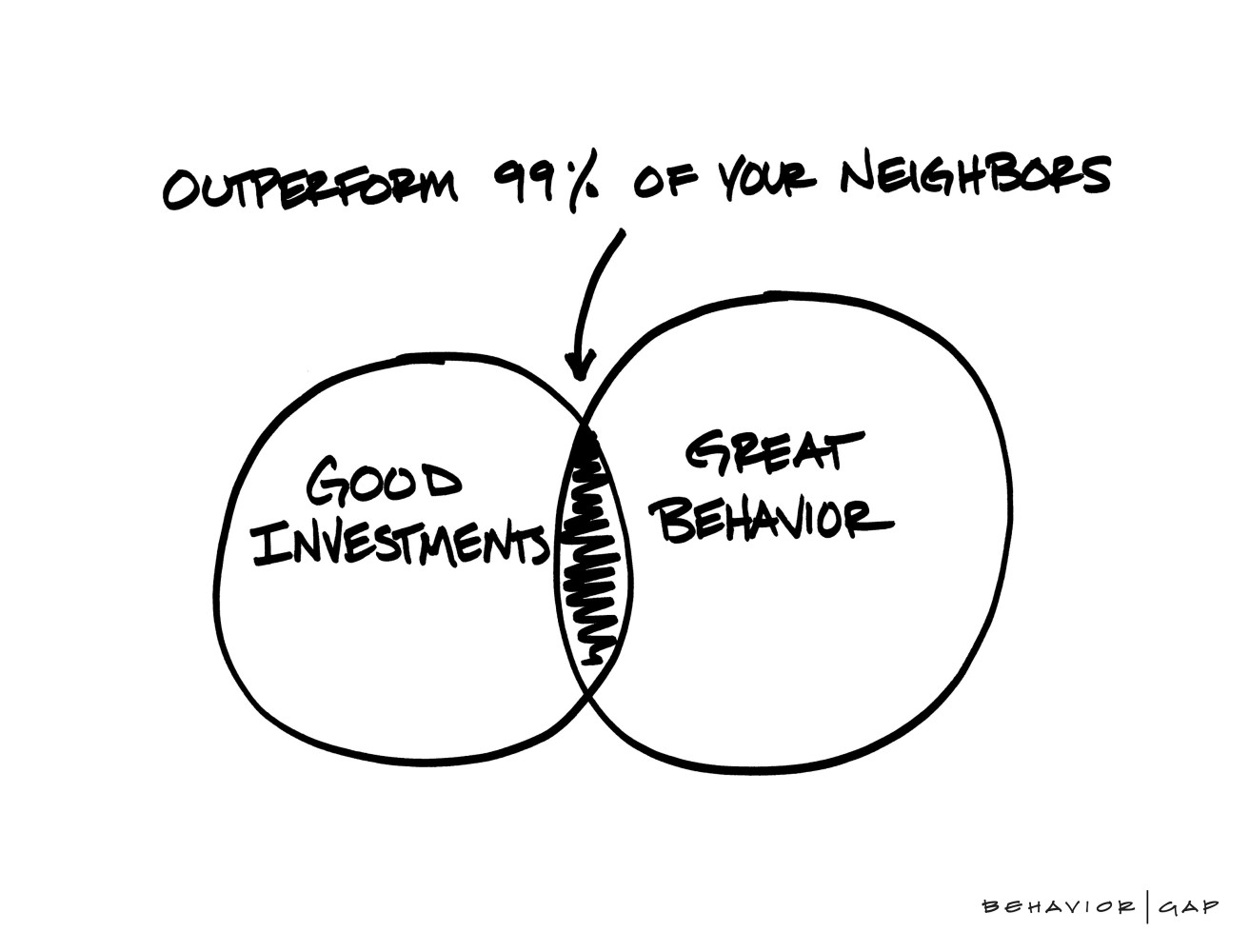

Investor behavior has been shown to be one of the largest determinants of outcomes or performance over time. Whenever we enter an ‘economic crisis’, we get an itch. It feels like we should do something to scratch it, and sooth the pain or ‘fix’ our approach to investing.

Our behavior as investors is one of the largest determinants of long-term success in investing. Great investments with poor implementation – like zigging and zagging in and out of the market is a recipe to underperform a more simplified buy and hold using mediocre investments.

The average person is not expected to know the futility of all this – they are expecting that this is vetted, and they want help making smart decisions with their money.

By omitting the important piece of information – that nobody really knows and how whatever event we are in now is just one event of a long line of unknown events – the ‘Average Investor’ is mislead, and prone to make bad decisions.

Our behavior we can control – the markets we cannot.

We need to think of ‘normal’ as an endless series of unknowns that we are in the middle of.

Controlling our behavior is how we as investors will stand the test of time.

Whatever crisis or opportunity of the day is only the one before the next.

This is how we need to think of normal – filled with unknowns and infinite possibilities.

Nobody is going to successfully trade their way through the next 3.75 years of Trump’s presidency, or afterwards, no matter how confident and well dressed the presenter seems.

The same person will be writing in six months about how ‘we’re entering uncertain times’ and ‘well, who could have expected [next big event] to happen’.

Assuming a proper plan is in place – we’re better served by ignoring the crisis commentaries and doing nothing.

Always remember that nobody knows what’s going to happen next. The markets are voodoo – and that’s ok.

Discussion